“It takes nerve not to flinch from or be crushed by the sight of one’s own shadow. It takes courage to accept responsibility for one’s own worst qualities.” –Edward C. Whitmont, from “The Evolution of the Shadow,” in Meeting the Shadow

It’s not easy to look at your own shadow.

In order to make our parents happy we started covering up parts of ourselves before we could walk. And we definitely knew the difference between approval and disapproval before we could talk. It’s a basic survival skill. We can’t make it on our own as infants. We have to depend on the goodwill of others. So if we hear we’re too much trouble, or our poop stinks, or we’re too lively or too clingy or too stupid, we learn to stuff those parts down into our shadows very quickly. By second grade, hiding parts of ourselves in order to please other people has become second nature.

Which is not necessarily a bad thing. In order to become a thinking human being who can cooperate with other thinking human beings, some of that old animal instinctual nature needs to be controlled. “Letting it all hang out” just won’t work among intelligent mammals who’ve been honing their warfare skills in dominator societies for thousands of years.

So a bit of repression serves a useful purpose. It allows children to become functioning, cooperative members of society. We learn not to drown our baby sister, or hit our brother over the head with a baseball bat. We learn how to sit still and pay attention to others. We figure out that we are not the center of the universe. (Hopefully.)

But once we grow up, we have a responsibility to get curious about what happened to all that juicy emotional energy we’ve been repressing since childhood. Otherwise, we’re liable to end up becoming a danger to society anyway. For when we refuse to admit that we even have certain feelings, we exclude the possibility of dealing with those feelings rationally. If we don’t take any notice of—or responsibility for—whatever lurks in our shadow, then we set other people up for ambush by our unsupervised inner demons.

In the famous book by Robert Louis Stevenson, Dr. Jekyll was a perfect gentleman, a widely respected, highly cultured, upper class, sterling citizen who spent most of his daylight hours ministering to the poor and needy. Afraid to mar his perfect image, but full of unappeased desires—this was back in the Victorian age, you know—Jekyll created an alternate ego, Mr. Hyde, to act out the less respectable urges in his soul. Bad idea. Because when Hyde slipped out the laboratory door at night and headed straight for the seediest parts of London, Jekyll had no control over him. As time went on and Jekyll kept denying his influence, Hyde’s desires took ranker and ranker forms. He persecuted prostitutes, preyed on the weak, even committed murder. Disavowed by Jekyll’s civilized side, Hyde grew ever more warped, ever more bestial, ever harder for Jekyll to manage. Eventually? You know it. Hyde took over. Jekyll became all Hyde, all the time.

There’s a recurring theme in movies and literature about taming the Beast, about soothing the savage soul. But for that to happen, someone in the story has got to pay attention to the poor old Beast. Conscious, thinking attention. And as in the outer world, so in the inner world: no creature thrives on neglect. No critter likes to be caged.

There’s a basic psychological rule that any instinctual character prowling around in your psyche will act better and be easier to handle if you can (1) admit that it exists, and (2) figure out what it wants. Then you can open negotiations with it. Then you can manage it without harming others. What’s the first step in AA’s famous 12-step program? Admitting you have a problem.

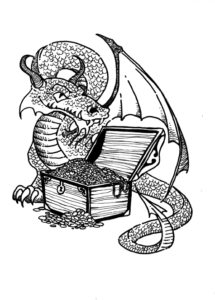

Let’s use selfishness as an example. We have a good strong symbol for selfishness in Western folklore—a dragon hunched over his hoard. Now dragons never actually use the treasure they steal. They just hoard it. Take it from other people, pile it up in a cave somewhere, and lie around on it. Fly out and terrorize the countryside occasionally. Breath fire. Eat whole cows and coy maidens.

Can we better manage our internal dragon of selfishness by pretending not to be selfish, I’m not being selfish! I deserve a bigger piece than you do! Or by keeping an eye out for our selfishness, so that, when we catch ourselves being selfish, we can just admit it, maybe even laugh at ourselves as we see it happening? Geez, look at that! Cut my piece of pie a lot bigger than yours, didn’t I? I’m such a rascal. Here, let me divvy this up better.

That might work. But if we go around trying to pretend that we’re not selfish, then we’re never going to be able to stop being selfish. We’re never going to have an accurate picture of who we are or what we’re doing. Plus, we’ll have a lousy sense of humor. Where it starts to get ugly is: we’ll have to keep other people distracted, probably by accusing them of being selfish first, so they’ll be too busy defending themselves to notice how much bigger we just cut our own piece of pie.

What a lot of work for a little more dessert! And of course—and most importantly—the chance to appear free from all flaws. In black/white, either/or cultures which are quick to judge and harsh to condemn, children learn that it is very important not to be caught in the wrong, at a very young age.

But, alas… our old dragon of selfishness will only get bigger and more demanding the longer we pretend not to know anything about him. Like a troll under a bridge. Like Hyde. In fact, left alone without supervision, our internal dragon of selfishness will eventually get loose and swoop out over the countryside, torching people and grabbing whatever he wants. And if caught, he will always have good, solid reasons for his behavior. The Dragon of Selfishness can morph into The Victim of Circumstance in an eye blink.

The trick is to look within once in a while and admit that our internal dragon really is selfish, and that he really is a member of our psychic zoo. If we can do that, if we can even manage to say something directly to him occasionally like, “Oh, there you are. I see you, you greedy old thing,” maybe throw him a juicy steak or buy him a new toy, then the dragon of selfishness will settle down and go back to sleep. If we just allow him a little conscious space once in a while—not let him get away with anything, just acknowledge that he’s there—then he won’t have to torch or hoard or get 50 feet long or max out the credit card or have an affair or cheat on exams or embezzle company funds to get our attention.

“Medieval heroes had to slay their dragons; modern heroes have to take their dragons back home to integrate into their own personalities.”–Robert Johnson, Owning Your Own Shadow