October is the month many of us start watching horror movies old and new. It’s a way of transitioning from summer to winter, a ritual for bidding goodbye to sunny days and embracing long dark nights that make the setting of a Tim Burton movie look positively cheerful. My all-time favorites are Kenneth Branaugh’s Frankenstein, Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula, and Shadow of the Vampire, where John Malkovich plays the obsessed director of Nosferatu and Willem Dafoe plays an ancient vampire. EXCELLENT movie. Things get nice and dark when the human director is more evil than the actual vampire. And I have to mention James Whale’s 1935 Bride of Frankenstein, too. Love that hisssss from Elsa Lancester at the end.

Thus, October is the month to think about vampires. They’re everywhere these days! But, why is this myth so prevalent? Why have vampires become one of our most enduring archetypes?

Because we all know in our bones—oops, in our blood—that vampires are real. Because each one of us has been sucked dry. And because we have each done some sucking ourselves.

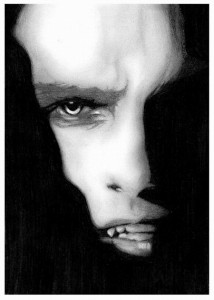

A real live vampire doesn’t wear a cape or have eyebrows like Bela Lugosi. A real live vampire is just an ordinary, everyday person who goes around sucking all the juice out of other people. He’s the perpetually disgruntled guy whose mood subdues a whole room full of otherwise cheerful folk. She’s the one who can’t get enough attention, can’t get enough love, can’t get enough praise. A real live vampire is that person who leaves you exhausted and drained after every visit. The one who talks and talks and talks, but never listens. The one grabbing for control in every situation.

And of course the ranks of ordinary vampires are swelled by the truly diabolical among us, the genuinely unbalanced: sociopaths, psychopaths, narcissists, borderline personalities… those who only see others as means to an end. These are the vampires that keep us up at night, the often charismatic world-wreckers who charm legions of followers into supporting their nefarious causes, and pass their dis-ease on to others, generation after generation.

Here’s what the Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism has to say about vampires:

The vampire is a strange phenomenon of the imagination, a shapeshifter, hypnotist and captivator, erotic and chillingly repugnant at the same time. He or she is often ravishingly, irresistibly seductive. That the vampire is also represented as a form of were-animal, fanged and nocturnal, suggests that as a psychic factor it shuns the light of consciousness, manifesting in the twilight of the subliminal as a sexual compulsion or another form of raw, insatiable hunger that cannot be put to rest and eventually takes possession of the whole personality. Some have compared the vampire to the “hungry ghost,” the revenant of unmetabolized deprivation and trauma, which obsesses us, keeping us out of life. The most deadly aspect of the classic vampire is that it can replicate its condition in its victims, who then also become the melancholy, exhausted, or restless “dead.”

More contemporary portrayals have idealized the vampire as a being of pale, lunar beauty, in whom soulfulness, wisdom and magical powers combine with exhilarating animal instinctuality. In this version, because the vampire lives forever, it can teach us the lessons of history. The human and vampire lovers of the Twilight series reflect the youthful romance between consciousness—which involves process and change—and the alluring fantasy of physical perfection, immutability and immortality. But though the vampire can never again become human, a human can become a vampire, suggestive of our vulnerability to the wholly absorbing nature of desire.

—The Book of Symbols, edited by Ami Ronnberg and Kathleen Martin. Germany: Taschen, 2010. Page 700.

Drains a living person… hypnotist, captivator, irresistibly seductive… shuns the light of consciousness… subliminal compulsions… insatiable hungers… revenants of deprivation or trauma… replicates its condition in the victim… an alluring fantasy of physical perfection and immortality…

We have a fascination with vampires because real live vampires walk among us.

But of course we can’t see them when we look in the mirror.